Because We Can and Because We Must

Words by Denise L. Mc Iver

“Until the prey can tell his/her side of the story, the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

African Proverb

Not long after the murder of George Floyd at the hands of officers of the Minneapolis Police Department, a flurry of well-meaning ‘Statements of Solidarity’ were disseminated by arts organizations, foundations, and other nonprofits, as well as for-profit companies and corporations. I actually started to collect some of them because I believed their sentiments were sincere.

I also found it interesting that white folks were only now becoming ‘Woke,’ when the murder of Black men and women is nothing new, given the systemic racism that has been historically perpetuated and even codified in the United States — that is, until the addition of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution outlawed slavery. Having a law on the books abolishing slavery is one thing; executing and following the rule of law is something else entirely.

George Floyd’s murder was only the latest (until the recent shooting of Jacob Blake, Jr.), and the horror of his death was available for all to see, thanks to cell phone footage. If nothing else, Floyd’s untimely death reignited difficult discussions about race and the enduring legacy of slavery in America. These discussions are not finished, and we have yet to carve out a plan to right the wrongs that have been thrust upon the descendants of the formerly enslaved.

As a Race Woman, a woman of color, and as a professional librarian who is committed to preserving to Black History, I am thrilled that our predominantly white, mainstream cultural institutions are taking a stand to support the study of Black Life. Libraries, archives, and other repositories (in mainstream as well as POC and culturally-specific institutions) that collect Black material culture must go even further. It is up to Black archivists and our allies who are committed to the cause at these institutions to make a serious and concerted effort to collect, organize, and make accessible the lived experience of Black people.

I am a major proponent of community archives and before the Covid-19 shutdown, I was a presenter, along with colleagues from The Huntington Museum and Library, Self-Help Graphics, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), at the 2020 convening of the annual conference of the California Associations of Museums. During our presentation, we discussed why community archives are important and provided concrete steps (see document) of how to begin. I believe we were successful in describing how to make it all happen, and the attendees seemed eager to begin their own programs at various California institutions.

I grew up in Ossining, New York. Ossining is probably best known for Sing Sing Prison (where Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were executed in 1953), and the Catholic convent Maryknoll. You may have heard of this small Hudson River town and village, which supported King George III and the British troops during the Revolutionary War and used the Hudson to transport arms. Mobsters used Ossining as a pit stop as they moved illegal alcohol down the Hudson to their speakeasies in New York City during Prohibition. The lead character of Mad Men, Don Draper, lived in Ossining which was a typical early 60s bedroom community.

My family and extended family members were working-class poor (though I didn’t realize that growing up—we had all the things white folks had, just less of them). Our parents, high school grads only, worked on the Fisher Body assembly line assembling Cadillacs, while our mothers cleaned the homes of the wealthier class. Still, our lives were rich and robust in terms of the wholesomeness of the Village of Ossining. As an adult, I came to understand that it does, indeed, take a village to raise a child.

I moved back to Ossining in 2006 and shortly thereafter started to pursue my MLIS studies at St. John’s University on an IMLS Scholarship. One afternoon, I decided to visit the Ossining Historical Society. The purpose of my visit was to review materials in the Society’s archives that highlighted Ossining’s Black residents. There, I found little to nothing. I thought this lack of information was my fault, that somehow I wasn’t conducting a thorough enough search. I just knew the historical society had to have something. I knew that my paternal grandfather, Charles H. Mc Iver, was part of The Great Migration, leaving Sanford, North Carolina to settle in this river town just after the turn of the century. My grandfather, who attended Livingstone College in North Carolina, was one of the six million who left the Jim Crow South to pursue his destiny in the North.

Image of the author, her mother, and her paternal grandfather, Charles H. McIver, at the author's christening party.

During my visit to the Ossining Historical Society, I asked the white male volunteer managing the Reading Room if he could tell me where to find materials on Ossining’s Black residents. He looked at me as if I were speaking Latvian.

This experience told me that collecting the histories of Ossining’s Black residents wasn’t a priority, nor did they seem to care. I was not only disappointed but angry. It was as though an entire segment of Ossining’s population never existed. The histories of my family, our family friends, and our churches were either ignored, considered irrelevant, or deemed unworthy of collecting and sharing. Once more, I had evidence that, at least in this situation, Black lives didn’t matter. And today I wonder how many other small town historical societies do not find it important enough to make a concerted effort to collect the histories of their Black residents.

Fortunately Victoria Gearity, Ossining’s Mayor, recently appointed Joyce Sharrock Cole as the Village of Ossining’s Historian. “Joyce has been on my radar for a couple of years. Her appointment to be Village Historian was only a matter of time. The right moment presented itself this summer,” said Mayor Gearity. She added: “During the wake of the George Floyd murder, Ossining residents hosted forums, rallies, and marches in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. My colleagues and I in Village government welcomed the opportunity to amplify Black voices.” Sharrock Cole, who also serves on Ossining’s Historic Preservation Commission, has been tasked with collecting the histories of Ossining’s entire community, including the town’s remaining Black elders. Additionally, as Ossining’s Historian, she will establish a fuller archival footprint of Ossining’s fascinating history.

Currently, Sharrock Cole is in the process of developing a more robust community-focused collecting program so that Ossining’s history gets its due. In the short span of three months, she has already initiated a Covid-19 Collection Initiative recruiting local high school students to collect stories and create metadata based on the same. She has already found evidence of a Black women’s social club called Les Bonnes Amies, comprised of Black women, many of whom were domestics, who were dedicated to raising funds to send Black high school graduates to college. Perhaps the most interesting story she’s unearthed is that of a group of Black men who amassed enough money to purchase a large plot of property on which to build a social club aimed at attracting the town’s Black upper-class. This club was so large that it could hold nearly 3,000 people. Unfortunately, Klan sympathizers torpedoed their plans.

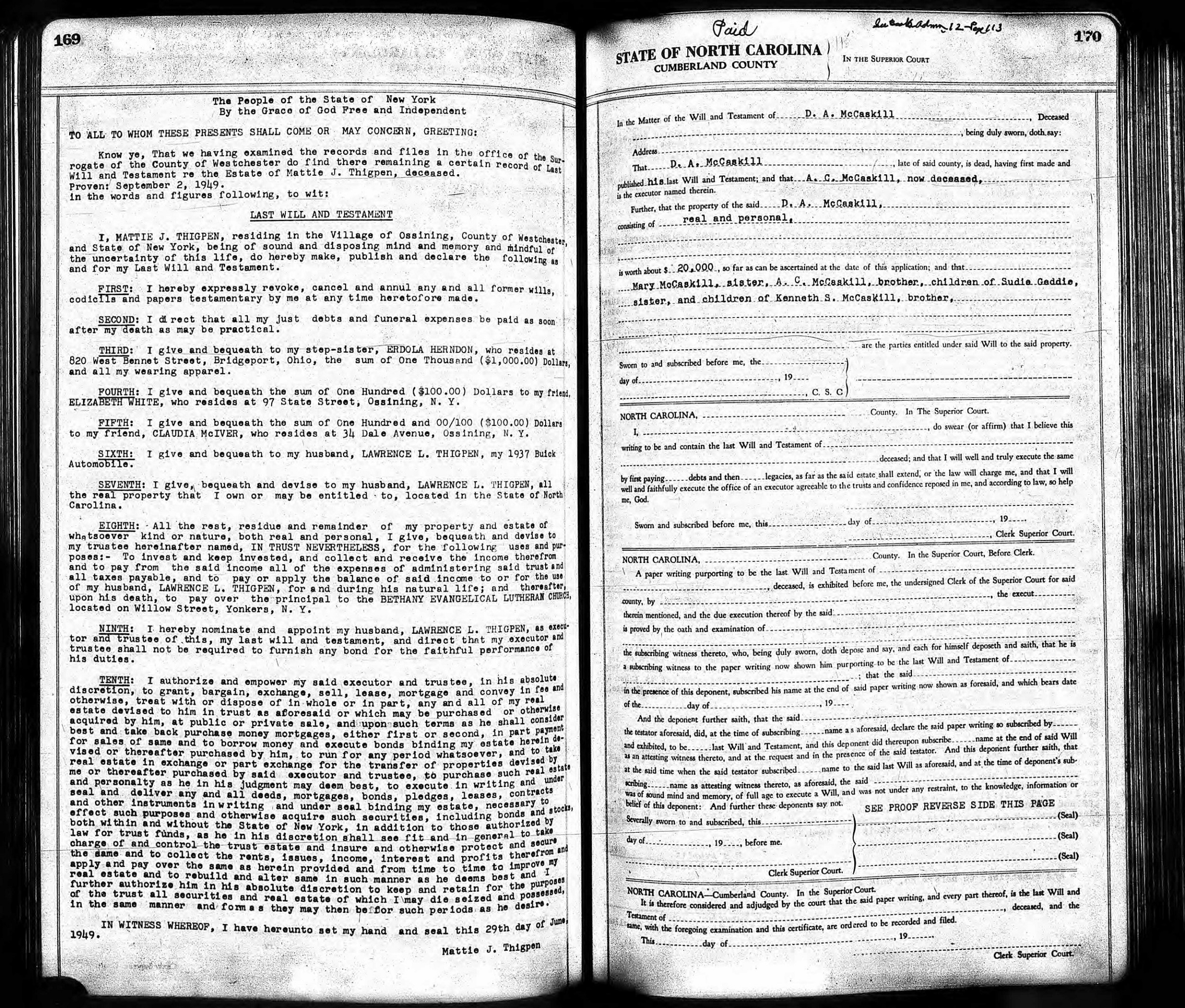

Sharrock Cole also found the Will of Mrs. Maddie Thigpen, in which Mrs. Thigpen promised $100.00—over $1000 in today's dollars—to “her good friend”, my paternal grandmother, Claudia Johnson Mc Iver.

Will of Mrs. Maddie Thigpen.

This past summer she met with my first cousins and spent a hot afternoon perusing a massive amount of our family’s memorabilia. She sent me photographs of my grandfather’s essays, written sometime in the late 1920 or early 1930s. I’m now transcribing these handwritten documents, which I hope will be used in an online exhibition in the future.

I’m serving as an advisor to Sharrock Cole, and helping target Ossining’s remaining Black elders so that their lived experiences are made known. Why? Because they are worthy, because we can, and, most importantly, because we have a duty to preserve their stories.

I believe that you, our progressively-minded allies, truly believe that Black Lives Matter in the archival space. Help us by sharing your knowledge in the creation of community archives, developing collaborative relationships with Black archivists and historians, sharing information about funding opportunities, and helping us train the next generation. That’s how you build capacity that engenders control. That’s how you ensure that our history—my history—is kept alive. And for that, collectively, we thank you.